What to Think About Bonds Now

It’s been awhile since we’ve talked about bonds, and recent headlines have suggested that bonds may be entering a bear market. So we’d like to share our thoughts about the bond market and—very much related—the Fed’s recent decision to raise interest rates by 0.25%.

Before we get into the data and the details of the economics of bonds, here’s the summary.

• In our current investment strategy, we regard bonds as a risk control measure first, an income generation tool second, and a capital appreciation strategy not at all. We rarely buy bonds with the expectation of high returns. We look to stocks and (to a lesser extent) real estate securities to enhance returns.

• We’ve believed for several years that the risk/reward ratio for bonds has been uniquely unfavorable. In our current investment strategy, we regard bonds as a risk control measure first, an income generation tool second, and a capital appreciation strategy not at all.

• As a result, we’ve kept bond maturities short and bond quality high. We’ve chosen bond investments that we expect to be less volatile and less risky. We’ve also reduced our bond holdings and increased our cash holdings.

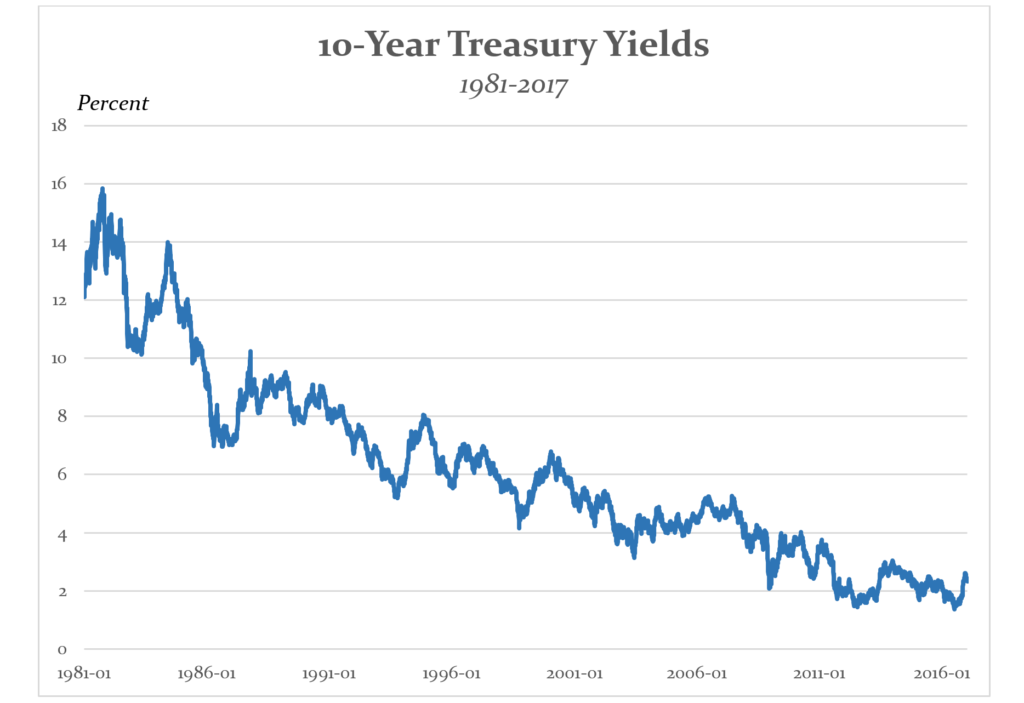

Let’s start by looking at the data. Last fall, a sharp uptick in interest rates reduced bond prices, a decline greater than the income received by bondholders, hence the negative returns. From September 1 through January 15, the Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index, a proxy for the universe of US government and corporate debt, fell by 2.7%. Most of that move (-1.8%) occurred after the election. Compared to a bear market in stocks, defined as a 20% decline, the recent move in bonds barely qualifies as a rounding error. But in the context of the long bull market for bonds that began in 1981, this sort of decline is unusual.

The relationship between interest rates and bond prices is an inverse one; when interest rates decline, bond prices rise, and vice-versa. When interest rates are historically low, as they have been for the last several years, any rise in rates means bond prices will fall.

While it is possible for interest rates to move lower, and even into negative territory (both European countries and Japan have seen negative rates) there is a fundamental risk/return asymmetry here. Even after the recent rise, bond yields remain very low. With more room for interest rates to increase than to fall, the possible benefits from falling interest rates are smaller than the potential cost of rising interest rates.

We expect interest rates to go up over the next few years, for several reasons.

• Short-term rates have been kept low by Federal Reserve policy. The Fed has now signaled that it expects to raise short-term interest rates (the Fed funds rate) several times more over the next year.

• Long-term rates have been artificially reduced by Federal Reserve open-market purchase activity. The Fed completed its formal policy of bond buying (Operation Twist) in October of 2014, but bond market activity has continued to a lesser degree.

• Without Fed intervention, the primary driver of bond prices and yields is likely to be inflation expectations.

How high might interest rates rise? This will depend on two factors: economic growth and inflation. Right now, the markets appear to anticipate that Trump’s economic program will lead to higher growth, more demand for capital and ultimately to higher inflation.

So what have we done to protect our clients? For starters, and more than a year ago, we reduced bond positions. A portion of the cash in our clients’ portfolios has come from the reduction of our bond allocation. We’ve actually gotten some pushback from clients against holding so much cash at near-zero returns. The recent fall in bond prices, we believe, demonstrates the reasons we’ve kept cash high and maturities short.

Holding cash has two benefits. We reduce exposure to capital losses, while retaining the ability to buy investment assets when prices (and hence opportunities) become more attractive. This is the “optionality of cash” we’ve discussed with many of you.

Next, we’ve shortened the duration of our bond portfolios. Duration is an approximate measure of a bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates and is related, but not equivalent, to the length of time to maturity. By owning more short- and intermediate-term bonds, we made a trade-off. We sacrificed current income to reduce the risk in a potential rising rate environment.

Finally, we’ve tilted toward higher-quality bonds. In particular, we’re continuing to increase our holdings of Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), a type of US government bond that features explicit protection against inflation. Right now TIPS are pricing in only 1.5% inflation over the next ten years. If inflation is higher, our TIPS positions should perform better.

Bonds are not the only asset class where the risk/return relationship is asymmetrical. We’ll continue to balance investment trade-offs to help our clients achieve financial success, and we appreciate the trust they place in us.

If you’d like to know more about bonds, or about the balance of risk and reward in your portfolio or in general, we welcome those conversations.

By James S. Hemphill, CFP®, CIMA®, CPWA®/ Managing Director & Chief Investment Strategist

Jim has been a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional since 1982. Jim specializes in complex wealth transfer and retirement transition strategies and coordinates TGS Financial’s investment research initiatives.

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by TGS Financial Advisors), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this article will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this article serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from TGS Financial Advisors. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. TGS Financial Advisors is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of this article’s content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the TGS Financial Advisors’ current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request.